Contents

Content Type: 1

Title: TED Talks in Lots of Languages

Body:

TEDx talks are given all over the world, in a wide variety of languages. Find excellent authentic content in your target language by browsing TED talks by language: http://tedxtalks.ted.com/pages/languages

Source: TEDx

Inputdate: 2016-03-06 21:19:43

Lastmodifieddate: 2016-03-07 03:28:22

Expdate:

Publishdate: 2016-03-07 02:15:01

Displaydate: 2016-03-07 00:00:00

Active: 1

Emailed: 1

Isarchived: 0

Content Type: 3

Title: Interpersonal Communication and Endangered Languages

Body:

by Lindsay Marean, InterCom Editor

Our InterCom topic this month is interpersonal communication. The proficiency-based approach supported by the NCSSFL-ACTFL Global Can-Do Benchmarks breaks language proficiency into three modes: presentational (speaking and writing), interpretive (listening and reading), and interpersonal communication. Interpersonal communication is of special interest because it is often students’ primary goal. In my own work with endangered North American indigenous languages, I often hear people say, “I just want to have a normal conversation about everyday things.” However, “everyday things” in “normal conversation” turn out to be difficult when working with a language that hasn’t been spoken widely for several generations. In some cases language communities must make use of archival materials: recordings of their ancestors speaking and linguists’ field notes. Such materials are usually presentational speaking: traditional stories and anecdotes told by one person to a tape recorder or researcher’s pen and notebook. Even when a community has access to first-language speakers, if a language is no longer transmitted from adults to children then speakers may struggle to talk about e-cigarettes, crowdfunding, and jeggings. Also, as new forms of interaction emerge, such as texting and email (see last week’s Topic of the Week article by Julie Sykes), speakers and learners may be uncomfortable navigating new media without established target-language norms.

Here are some ideas for expanding and improving proficiency in interpersonal communication in endangered languages that may be of use in other contexts as well, such as teaching heritage learners or when the teacher’s own proficiency is limited:

- Create opportunities for speakers and learners to interact in the target language. Consider immersion weekends or camps, immersion sets in master-apprentice pairs as pioneered by the Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival, speakers’ tents at community gatherings, and dedicated time for conversation in classes and teacher training programs.

- UNESCO’s Ad Hoc Expert Group on Endangered Languages considers “response to new domains and media” to be one of nine factors in assessing language vitality. Encourage community language activists to text and email each other in the target language. Many language communities have pages on social media where only the target language is used. Some elders embrace email and Facebook because of their potential for communication in spite of diaspora or hearing loss . As a learner, I appreciate the extra time I have with asynchronous communication; I can look words up and check my verb inflections before I hit “send.”

- Growing a language’s lexicon is often controversial within a community. Some language activists promote borrowing words for new things from the dominant language. In the words of Potawatomi elder and speaker Jim Thunder, Sr., “There is no need for us to make up words to fit the English language, since everyone already knows the English terms for those words.” Others embrace the process of creating new words; for example, the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma and NASA collaborated to create an Earth and Sky curriculum that includes words for “Mars rover” and “Saturn." Both approaches are natural processes in healthy languages. In this week’s Activity of the Week I describe how we used a game to grow our vocabulary as a scaffolding activity for a larger project.

- Culture-bearers are fantastic resources for learning interpersonal norms, even if they don’t speak the heritage language themselves. For example, “What is your name?” may not be used in your heritage language because it is more normal to ask someone you know who a stranger is instead of asking the stranger directly.

To summarize, the best way to build proficiency in interpersonal communication is to fully embrace it in all domains and media. Enjoy using your language!

Source: CASLS Topic of the Week

Inputdate: 2016-03-07 16:23:40

Lastmodifieddate: 2016-03-14 03:28:43

Expdate:

Publishdate: 2016-03-14 02:15:01

Displaydate: 2016-03-14 00:00:00

Active: 1

Emailed: 1

Isarchived: 0

Content Type: 4

Title: Salad Bowl

Body:

I have the privilege of working with the Pakanapul Language Team in the area of Lake Isabella, California. Every spring Whiskey Flats Days, a historical reenactment festival, takes place in nearby Kernville. We wanted to talk about Whiskey Flats Days, but realized that we didn’t have the necessary vocabulary. To develop our vocabulary, we played a game commonly known as Salad Bowl.

Mode: Interpersonal Communication

Learning Objectives:

- Students will be able to use circumlocution and non-verbal cues to communicate ideas that they don’t know the vocabulary for.

- Students will develop and use vocabulary around a specific topic.

Materials Needed: notecards with target vocabulary words written on then in English (or other dominant language), bowl to draw cards from, timer

Procedure:

- Draft a list of the vocabulary that you anticipate you and your students will need to talk about a chosen topic. In our Whiskey Flats Days example, we had the following: parade, team roping, barrel racing, rodeo, concert, band, kids’ games, gunfight, actor, play (theater), carnival, encampment, costume contest, mayor, charity, car show.

- Write one English word or phrase on each note card. Fold the notecards and put them into a bowl.

- Divide class into two teams. A person from Team A will have one minute to get his/her teammates to guess as many cards as possible, drawing a new card from the bowl as soon as teammates say the word. After a minute, a person from Team B will have a turn with his/her own teammates. Once all of the cards have been drawn from the bowl, tally up to see how many cards each team guessed during that round.

- There are three rounds.

- Round 1: Taboo. The person drawing cards speaks only in the target language (no English) to describe the word on the card.

- Round 2: Charades. Put all of the cards back in the bowl, and mix them up. The person drawing the cards must act out the English word or phrase. This will be easier because both teams now know what all of the cards in the bowl are.

- Round 3: Single Word or Gesture. Again put all of the cards back in the bowl. This time the person drawing the cards is limited to a single word or gesture.

- Now that everyone is familiar with the new vocabulary to be explored and has seen some ideas for circumlocution or description, as a whole group discuss how you can say each word or phrase in the target language. If possible arrive at a consensus for how you will say it. Our group put the new target language words on post-its in a section of the room and left it there for a certain amount of time so that people could provide anonymous feedback, make other suggestions, etc. Then the words were re-visited before being adopted as our shared way to talk about these new things.

Source: CASLS Activity of the Week

Inputdate: 2016-03-07 20:08:37

Lastmodifieddate: 2016-03-14 03:28:43

Expdate:

Publishdate: 2016-03-14 02:15:01

Displaydate: 2016-03-14 00:00:00

Active: 1

Emailed: 1

Isarchived: 0

Content Type: 3

Title: Approaching the ‘Standard’ with Respect to Identity and Social Context

Body:

By Renée Marshall, Chinese Flagship and Oregon International Internship Program Coordinator

During the pre-service phase of my teaching career I witnessed an interaction that I will never forget. The class included a heritage speaker with an obvious enthusiasm and pride in his ability to help his classmates as he already spoke some Spanish. After the first vocabulary quiz his face visibly dropped when he saw his score. He carefully looked over his quiz and asked the teacher to clarify. He said, “pork is ‘puerco’ but you marked me down. And lunch is ‘lonche’ but it’s marked wrong.” The teacher responded that the correct word for pork is “cerdo” and that “puerco” was incorrect; in fact, it was not even “real Spanish” and the word “did not exist.” The student, clearly dejected, said under his breath, “I can’t believe I got an F. I'm a bad Mexican.” From that moment on his behavior in class changed markedly, no longer excited and helpful but rather sullen and disruptive.

This student’s life experiences and home language are equally as important and valid as the ‘standard.’ As educators, we want to prepare our students to communicate with as many different language communities as possible and in a variety of contexts. Knowledge of the ‘standard’ variety of a language is important, particularly in academic writing and speaking. The word “cerdo” will be more widely understood by Spanish-speakers across the world than “puerco,” just as with “almuerzo” versus “lonche.” However, it is unfair to say that “puerco” and “lonche” are not real words. They are commonly used in the Spanish-speaking communities that surrounded this particular school, and in many others. While not considered ‘standard’ Spanish words, they are used for daily communication in large communities; thus, approaching the ‘standard’ while not diminishing the importance and validity of identity and social context is key.

As I witnessed that day, teacher attitudes toward linguistic variation can have a profound effect on student attitudes. Listed here are three ideas of approaching linguistic variety with your language learners:

- Emphasize less on “right” and “wrong” and more on “depends on the context and to whom you are speaking.” For example, you can highlight the most commonly accepted form of a word or grammatical form, indicating that this form will be most widely understood, while also giving (or asking students for) other ways it is said or used in different contexts (countries, communities, situations).

- Actively encourage students to explore linguistic variation in the target language. Students could actively teach each other linguistic varieties, for example students teaching each other Louisiana French words and phrases, with their equivalent in ‘standard’ French. Students work with both the variation and the ‘standard’ version of the word or phrase, thus opening up their language repertoire to multiple contexts and linguistic communities.

- Have guided discussions in your class about language hierarchy and the power of language. A ‘standard’ form of the language helps people communicate with each other, but it can also be used to discriminate against groups of people who speak a certain way. As language, culture, and identity are intimately intertwined, people may make assumptions about a person’s socio-economic status, race, gender, sexual orientation, and geographical origin based on how that person speaks and writes. Language can be used politically by those who speak the dominant variation to keep power, bestow power, or usurp power from minority groups of people. As a result of language policies and attitudes towards language certain groups of people may be denied opportunities to find success in school, college, the job market, and social and political arenas. For example, it’s expected that you speak and write a certain way following certain rules to be accepted into college or to become the president of the United States. Creating awareness of these hierarchies, inequalities and discriminations is powerful. PBS.org's "Do you speak American" program discusses the above issues in the U.S. and offers further resources on the subject. Two contextualizing articles from the website are: "Language Myth #17: They Speak Really Bad English Down South and in New York City" by Dr. Dennis R. Preston from Michigan State University and "What is 'Correct' Language?" by Dr. Edward Finegan from University of Southern California.

Source: CASLS Topic of the Week

Inputdate: 2016-03-08 08:58:11

Lastmodifieddate: 2016-05-09 11:53:22

Expdate:

Publishdate: 2016-05-09 10:37:07

Displaydate: 2016-05-09 00:00:00

Active: 1

Emailed: 1

Isarchived: 0

Content Type: 5

Title: CASLS at The Language Flagship Technology Innovation Center

Body:

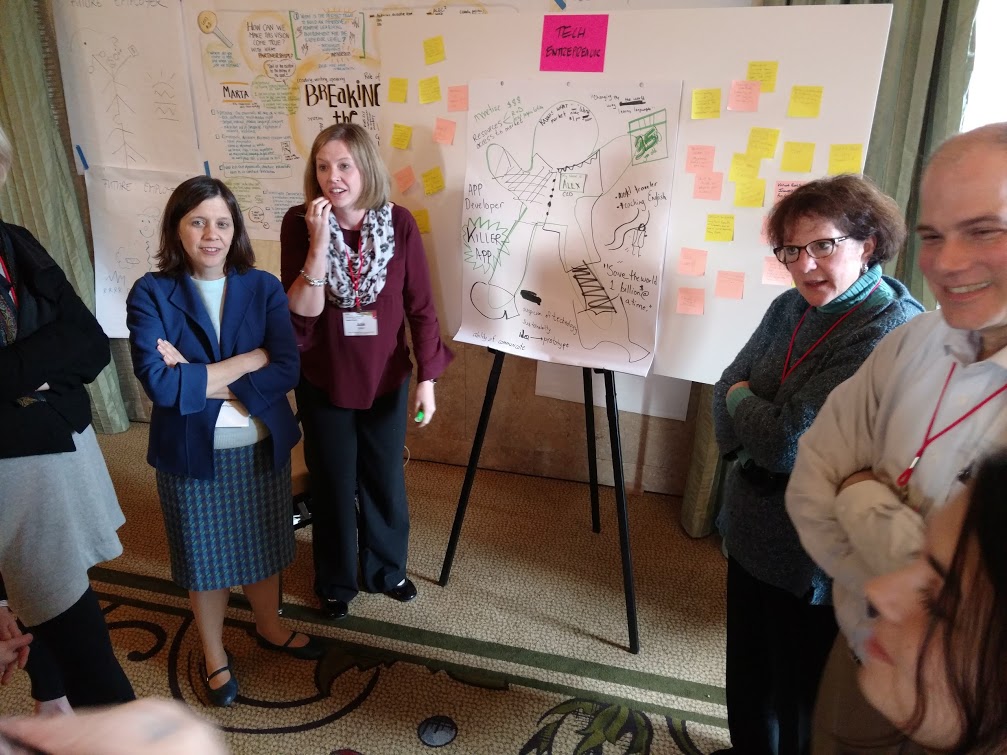

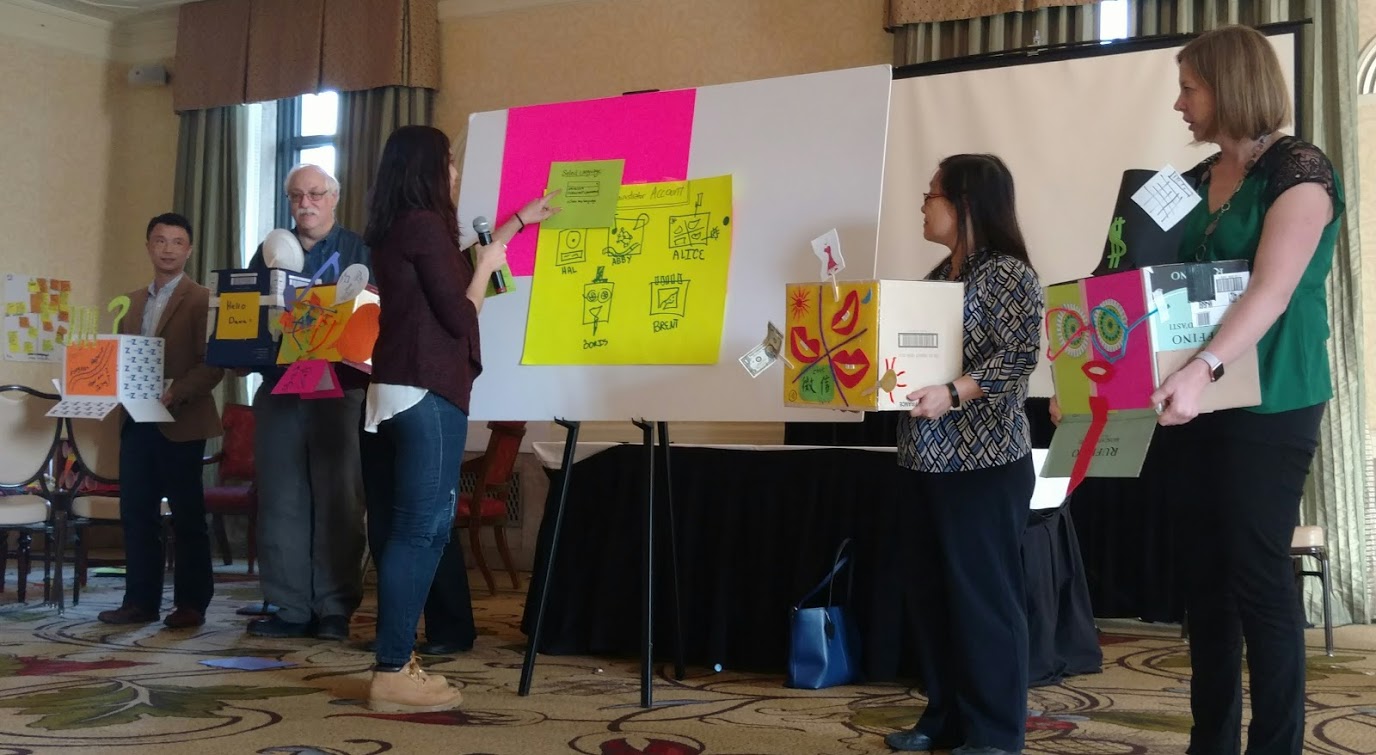

The Language Flagship Technology Innovation Center (http://lftic.lll.hawaii.edu/) started off its first year in the Planning stage by hosting three symposia, held in Honolulu, Pittsburg, and San Francisco. The focus this year is on strategic planning in incorporating the use of technology into language programs. The symposia, focused on design-thinking for innovation, bring together experts in the fields of language teaching, linguistics, and CALL/technology in education. Julie Sykes, CASLS Director, serves as a founding design team member, and says about the experience, "The Language Flagship Technology Innovation Center is a unique opportunity for experts in academia, business, and government to join forces to make transformational changes in technology and language education. It is exciting to be part of such a great endeavor." CASLS is enthusiastic about being involved in the development of this important foreign language teaching and technology intersection and is looking forward to continued work in this area in the years to come.

The Language Flagship Technology Innovation Center (http://lftic.lll.hawaii.edu/) started off its first year in the Planning stage by hosting three symposia, held in Honolulu, Pittsburg, and San Francisco. The focus this year is on strategic planning in incorporating the use of technology into language programs. The symposia, focused on design-thinking for innovation, bring together experts in the fields of language teaching, linguistics, and CALL/technology in education. Julie Sykes, CASLS Director, serves as a founding design team member, and says about the experience, "The Language Flagship Technology Innovation Center is a unique opportunity for experts in academia, business, and government to join forces to make transformational changes in technology and language education. It is exciting to be part of such a great endeavor." CASLS is enthusiastic about being involved in the development of this important foreign language teaching and technology intersection and is looking forward to continued work in this area in the years to come.

Source: CASLS Spotlight

Inputdate: 2016-03-08 10:57:17

Lastmodifieddate: 2016-04-04 03:41:34

Expdate:

Publishdate: 2016-04-04 02:15:01

Displaydate: 2016-04-04 00:00:00

Active: 1

Emailed: 1

Isarchived: 0

Content Type: 5

Title: Intercultural Pragmatic Interactional Competence Assessment

Body:

Imagine a language student on the computer interacting with an avatar either with voice and/or text in his or her L2. In the simulation the student needs to buy something from the store and must interact appropriately with the avatar to accomplish his or her goal. The way the student uses language in this scenario could tell the teacher about his or her decision making process and intercultural competence skills.

CASLS, in collaboration with AELRC, is currently working on the challenging task of creating a digital simulation to assess L2 learners’ abilities to interact in culturally appropriate ways. The two centers are designing, building, and validating the simulation, which is made up of lifelike scenarios designed to measure intercultural competence and appropriateness in a multilingual environment. This simulation is for students learning L2 in formal educational contexts and the purpose is to provide instructors with a profile of their students’ intercultural competence and enable them to provide students with appropriate instructional interventions.

This digital simulation assessment will be composed of three scenarios. The first is a peer-to-peer interaction where the student must make plans for the weekend with a friend but as the weekend gets closer a complication arises requiring negotiation. The second is a service transaction where the student must purchase a needed item. The third occurs in a school setting where the student must negotiate with the instructor about his or her school schedule for the upcoming year. The goal is that allowing students to interact in this simulated yet realistic digital space will shed light on learners’ ability to express and interpret meaning in situationally appropriate ways.

This project is called IPIC, intercultural pragmatic interactional competence, assessment. It’s intended for high school and university level students and will first be offered in Korean and Spanish. To learn more, visit the project page on CASLS’ website.

Source: CASLS Spotlight

Inputdate: 2016-03-08 11:22:51

Lastmodifieddate: 2016-04-18 03:29:56

Expdate:

Publishdate: 2016-04-18 02:15:02

Displaydate: 2016-04-18 00:00:00

Active: 1

Emailed: 1

Isarchived: 0

Content Type: 4

Title: Planning a Party

Body:

This activity was originally developed for an advanced high school Spanish class with the purpose of engaging learners in task-based, written interpersonal communication. The task that the learners are engaged in, planning a party, requires considerable negotiation and some target-language research in order for learners to arrive at an accord.

Learning Objectives:

Learners will be able to:

- Use vocabulary related to party planning appropriate to context.

- Research in the target language to inform decision making.

- Respect imposed limitations and arrive at an agreement when making decisions with a partner.

Modes: Interpersonal Communication, Interpretive Reading

Materials Needed: Computers with internet access, Gmail accounts for teachers and students, Decision Making Handout in Spanish or English

Procedure: Download the full lesson plan here.

Source: CASLS Activity of the Week

Inputdate: 2016-03-08 16:14:39

Lastmodifieddate: 2016-03-21 03:30:51

Expdate:

Publishdate: 2016-03-21 02:15:02

Displaydate: 2016-03-21 00:00:00

Active: 1

Emailed: 1

Isarchived: 0

Content Type: 4

Title: Waging a Complaint

Body:

by Sara Li

The purpose of this activity is to introduce English language learners to the pragmatic knowledge that is necessary to wage an effective complaint. This activity was designed for a classroom of learners at intermediate-low to intermediate-high proficiency levels.

Learning Objectives:

Learners will be able to:

- Prove comprehension of audio texts through effective note taking, main point identification, and reconstruction of the texts.

- Listen to audio texts and identify the interlocutors, main ideas, and the four steps in complaint dialogs.

- Prove understanding of the severity of a complaint through analysis of pragmatic features including intensifiers, swear words, and upgraders.

Modes: Interpretive listening, Interpersonal Communication

Materials Needed: Audio Text 1 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OV7SXmHq0Bk), Audio text 2 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cJQcxoXi5cg), Student Handout, ink pens in black, blue, red, orange, green, and yellow

Procedure:

- In small groups (no more than 5 members), learners brainstorm the characteristics of an effective verbal complaint. During this brainstorm, they should consider common words, common phrases, and other linguistic features including prosody (the rhythm and intonation of language).

- Next, learners verify their brainstorm by analyzing Audio Text 1. As they listen, they must take notes about and identify (1) the main problem; (2) the steps in turn taking that formed the complaint; (3) the steps in turn taking that formed the response to the complaint; (4) any changes in tone; and (5) the questions asked and the purpose behind those questions.

- In order to verify their notes, learners are given the dialog from Audio Text 1 in sentence strips that have been scrambled. They continue to work in small groups by using their notes to put the dialog back in order. They then verify that their dialog is in the correct order by listening to Audio Text 1 one more time.

- After that, learners listen to Audio Text 2 and repeat Step 2.

- As a class, learners briefly discuss what the differences are between the two dialogs (missing steps in developing the complaint, tone, use of swear words, emphasis, etc.).

- In order to ensure that all learners understand the pragmatic requirements of the two audio texts, they will then mark the transcripts of the two complaints by using the Student Handout. They will use (1) red ink to underline the start of the conversation; (2) orange ink to underline where the complainer states the problem; (3) yellow ink to underline where the complaint receiver clarifies the problem; (4) green ink to underline where the interlocutors make suggestions and take actions; (5) black ink to circle the similarities in both dialogs and draw stars to mark the differences; (6) red ink to circle the words or phrases that indicate how each interlocutor feels; and (7) blue ink to mark the place where the complainer restates/emphasizes his request or problem.

- As the learners work, the teacher should circulate through the room to provide feedback.

- To close this activity, learners participate in a class discussion in which they work together to decide which complaint sequence is more severe. They are to support this decision through analysis of tone, emphasis, swearwords, and the like. Teachers may find it beneficial to project some of the marked texts with a document camera during this discussion in order to help learners to justify their analyses with specific information from the text.

Notes: As a possible extension, teachers can have learners write or roleplay their own complaint scenarios in order to see if the students are able to emulate appropriate pragmatic behavior.

This activity can easily be adapted to lower or higher proficiency levels by adjusting the complexity of the audio texts. In this same vein, teachers may find that novice learners need to use their first language at times in order to analyze the discourse appropriately.

Source: CASLS Activity of the Week

Inputdate: 2016-03-11 07:58:00

Lastmodifieddate: 2016-04-04 03:41:34

Expdate:

Publishdate: 2016-04-04 02:15:01

Displaydate: 2016-04-04 00:00:00

Active: 1

Emailed: 1

Isarchived: 0

Content Type: 1

Title: Volume 19 Number 4 of TESL-EJ

Body:

Volume 19, number 4 of the online journal TESL-EJ is now available. This special issue on cooperative learning is available at http://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/

Source: TESL-EJ

Inputdate: 2016-03-12 13:05:58

Lastmodifieddate: 2016-03-14 03:28:43

Expdate:

Publishdate: 2016-03-14 02:15:01

Displaydate: 2016-03-14 00:00:00

Active: 1

Emailed: 1

Isarchived: 0

Content Type: 1

Title: March 2016 Issue of FLTMAG

Body:

The March 2016 of FLTMAG, a magazine on technology integration in the world language classroom, is available online at http://fltmag.com/category/march-2016/

In this issue:

Differentiation and Accommodations: Buffet Style Learning

VoiceThread and Universal Design for Learning

The Cross-Cultural Assessment of Disability

Teaching Languages to Students with Learning Challenges: The Role of Technology

Get on Board: Universal Design for Instruction

Braille, Banerjee, and Intel

Interview with Jean Bouchard, Director of the Modified Language Program at the University of Colorado Boulder

Source: FLTMAG

Inputdate: 2016-03-12 13:07:45

Lastmodifieddate: 2016-03-14 03:28:43

Expdate:

Publishdate: 2016-03-14 02:15:01

Displaydate: 2016-03-14 00:00:00

Active: 1

Emailed: 1

Isarchived: 0