View Content #19025

| Contentid | 19025 |

|---|---|

| Content Type | 3 |

| Title | "But My Language Doesn't Have a Corpus": Building and Using Your Own |

| Body | by Lindsay Marean, InterCom Editor One of my favorite languages is Paka’anil, an indigenous California language spoken and taught by fewer than a dozen Tübatulabal people in the area of Lake Isabella. There isn’t a large online corpus like the COCA for Paka’anil, and there are no published curricula like there are for major languages like Spanish and German. Among the available materials are a grammar written in 1935 by a young linguist named Charles Voegelin, and a collection of texts by the same researcher. The Tübatulabal community wants to speak Paka’anil the way their ancestors did, and we are all concerned that basing our learning on the grammar alone may lead us to speak in a way that is grammatically correct, but unlike the way first-language Paka’anil speakers really spoke. Corpus-driven instruction (CDI) is a promising tool for making more use of the text collection so that we can learn from the actual patterns of Paka’anil as it was spoken in 1935. I started by going through CALPER’s tutorial. This tutorial uses WordSmith to do the analyses, but since I use a Mac, I ended up using a different application, the UAM Corpus Tool.

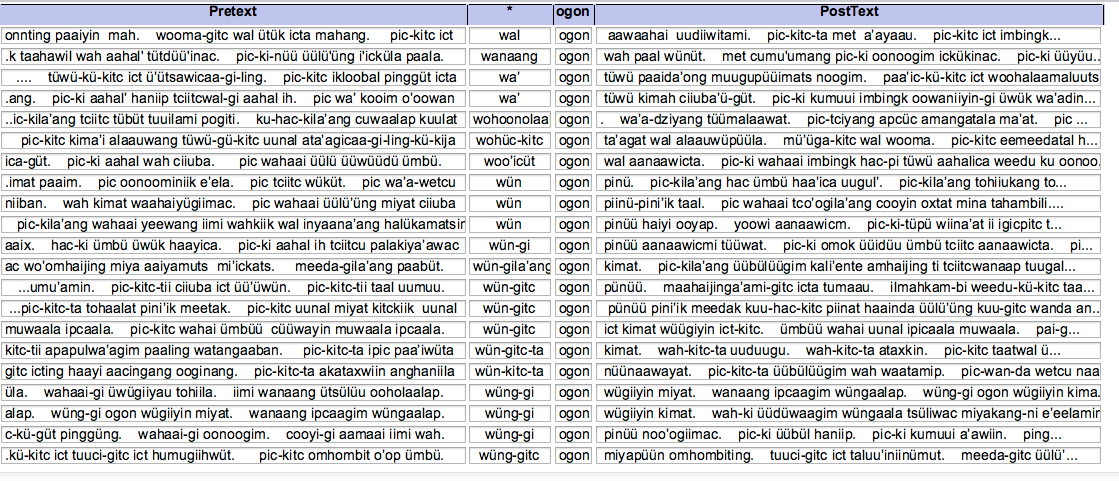

My next step was to do a concordance search to see what occurred before and after the word. In my small corpus, there are seven instances of a form of wün “be” followed by ogon followed by pinü “the same.” In other words, I found a common expression that I hadn’t known existed: wün ogon pinü “it is the same (some event happening).” I created an activity for the Pakanapul language team to work on together to practice using this newly-discovered expression in the appropriate context.

Of course, this single discovery only begins to explain all of the uses of ogon, to say nothing of everything else that we can learn about Paka’anil using a corpus. I learned a few lessons along the way: • Set aside some distraction-free time to be curious and explore the corpus. I hope that you, too, are inspired to try CDI in your own teaching and learning. |

| Source | CASLS Topic of the Week |

| Inputdate | 2015-02-19 12:25:08 |

| Lastmodifieddate | 2015-02-23 03:14:33 |

| Expdate | Not set |

| Publishdate | 2015-02-23 02:15:01 |

| Displaydate | 2015-02-23 00:00:00 |

| Active | 1 |

| Emailed | 1 |

| Isarchived | 0 |

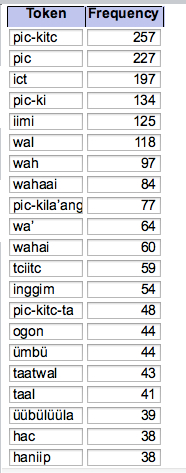

Following the instructions in the tutorial, I created a plain text file with all of the stories in Voegelin’s text collection. I wasn’t sure exactly what questions to ask, so I started by generating a list of the most common words. Most of the results weren’t very surprising: different forms of the word that means “then” or “and then;” “came” and “went;” and “coyote” (an important figure in Tübatulabal stories). However, the 15th most frequent word jumped out at me: ogon occurred 44 times; Voegelin translated it as an “empty word” or as a “particle with vague modal meaning.” Modern Paka’anil speakers rarely use this word; after all, how does one incorporate an “empty word” into one’s speech? However, its high frequency in these texts tells us that we can’t ignore this word any more; we need to figure out how it is used.

Following the instructions in the tutorial, I created a plain text file with all of the stories in Voegelin’s text collection. I wasn’t sure exactly what questions to ask, so I started by generating a list of the most common words. Most of the results weren’t very surprising: different forms of the word that means “then” or “and then;” “came” and “went;” and “coyote” (an important figure in Tübatulabal stories). However, the 15th most frequent word jumped out at me: ogon occurred 44 times; Voegelin translated it as an “empty word” or as a “particle with vague modal meaning.” Modern Paka’anil speakers rarely use this word; after all, how does one incorporate an “empty word” into one’s speech? However, its high frequency in these texts tells us that we can’t ignore this word any more; we need to figure out how it is used.